Hi Slashdot, read this, woulda ya?

Did you ever see that one Friends episode where they make up a game where they test their knowledge of each other? In one of the rounds, the girls are asked what Chandler does for a living, and the answer they come up with is “transponster!” Which of course isn’t a word. All they know is that he carries a briefcase. Well I suspect that many of my friends don’t know what I do for a living. I suspect, if asked, you’d answer something like “I think he fixes computers.”

I know jobs aren’t the most interesting topic, but in my continuing series on embracing my inner geek, I think its important to tell you all (you who are interested anyway) what happens at my job. If you’re at all interested in who I am, you should know what I do. And believe it or not, I don’t fix computers for a living.

In fact most employers I’ve worked for actually have rules in place to suggest that I not try to fix my own computer. There’s these organizations, some (not all) still stuck in the 70s and 80s, called “I.T. Departments” who’s official purpose is to fix computers — but who’s actual purpose is to attempt to prevent their users from doing anything dangerous (read: useful.)

I do not, and have never, worked in an “I.T. department,” although I’ve volunteered those skills I have in that area on many occasions. In actuality, my job is much different.

I am, in the States, known as a Software Engineer. In Canada we’re not allowed to call ourselves engineers, although the discipline is no less rigorous than any other kind of engineering.

But perhaps its for the best, because “engineering” describes only a part of what I do.

A software developer must be part writer and poet, part salesperson and public speaker, part artist and designer, and always equal parts logic and empathy. The process of developing software differs from organization to organization. Some are more “shoot from the hip” style, others, like my current employer are much more careful and deliberate. In my 8 years of experience I’ve worked for 4 different companies, each with their own process. But out of all of them, I’ve found these stages to be universally applicable:

Dreaming and Shaping

A piece of software starts, before any code is written, as an idea or as a problem to be solved. Its a constraint on a plant floor, a need for information, a better way to work, a way to communicate, or a way to play. It is always tied to a human being — their job, their entertainment… their needs. A good process will explore this driving factor well. In the project I’m wrapping up now I felt strongly, and my employer agreed with me, that to understand what we needed to do, we’d have to go to the customer and feel their pain. We’d have to watch them work so we could understand their constraints. And we’d have to explore the other solutions out there to the problem we were trying to solve.

A piece of software starts, before any code is written, as an idea or as a problem to be solved. Its a constraint on a plant floor, a need for information, a better way to work, a way to communicate, or a way to play. It is always tied to a human being — their job, their entertainment… their needs. A good process will explore this driving factor well. In the project I’m wrapping up now I felt strongly, and my employer agreed with me, that to understand what we needed to do, we’d have to go to the customer and feel their pain. We’d have to watch them work so we could understand their constraints. And we’d have to explore the other solutions out there to the problem we were trying to solve.

Once you understand what you need to build, you still don’t begin building it. Like an architect or a designer, you start with a sketch, and you create a design. In software your design is expressed in documents and in diagrams. Its not uncommon for the design process to take longer than the coding process.

As a part of your design, you have to understand your tools. Imagine an author who, at the start of each book, needs to research every writing instrument on the market first. You have to become knowledgeable about the strengths and weaknesses of each tool out there, because your choice of instrument, as much as your design or skill as a programmer, can impact the success of your work.

Then you review. With marketing and with every subject matter expert and team member you can find who will have any advice to give. You meet and you discuss and you refine your design, your pre-conceptions, and even your selected tools until it passes the most intense scrutiny.

Once you have these things down, you have to be willing to give them up. You have to go back to the customer, or the originator of the problem, and sell them your solution. You put on a sales hat and you pitch what you’ve dreamt up… then wait with bated breath while they dissect your brain child. If you’ve understood them, and the problem, you’ll only need to make adjustments or adapt to information you didn’t previously have. Always you need to anticipate changes you didn’t plan for — they’ll come at you through-out the project.

Once you know how the solution is going to work, or sometimes even before then, you need to figure out how people are going to work with your solution. Software that can’t be understood can’t be used, so no matter how brilliant your design, if your interface isn’t elegant and beautiful and intuitive, your project is a failure.

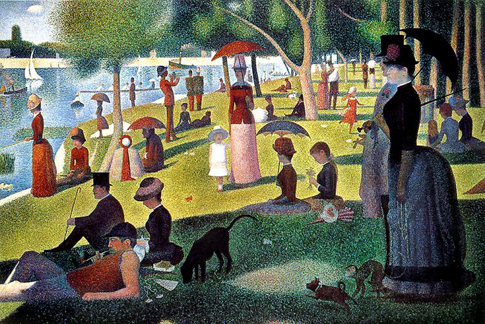

I don’t pick those adjectives lightly either. All of them are required, in balance. If its not elegant, then its wasteful and you’ll likely need to find a new job. If its not beautiful, then no one will want to use it. And if its not intuitive, no one will be able to use it. The attention to detail required of a good interface developer is on par with that of a good painter. Every dot, every stroke, every color choice is significant.

To make something easy to use requires at least a basic understanding of human reactions, an awareness of cognitive norms. People react to your software, often on a very base level. If you don’t believe me, think of the last time your computer crashed before you had a chance to save the last 2 hours worth of an essay, or a game you were playing.

What you put before your users must be easy to look at so that they are comfortable learning it. It must anticipate their needs so that they don’t get frustrated. It must suggest its use, simply by being on the screen. And above all else, it must preserve their focus and their effort.

So you paint, using PowerPoint, or Visio, or some other tool, your picture of what you think the customer is going to want to use, and once again you don your sales hat and try to sell it to them. Only, unlike a salesperson selling someone else’s product, you are selling your own work, and are inevitably emotionally-attached to it. Still, you know criticism is good, because it makes the results better, so you force yourself to be logical about it. Then finally, when your solution is approved, and your interface is understood, you can move on to the really fun part of your job:

Prose and Poetry

A good sonnet isn’t only identified by the letters or words on the page, but by the cadence, the meter, the measure, the flow… a good piece of literature is beautiful because it is shaped carefully yet communicates eloquently.

Code is no different. The purpose of code is to express a solution. A project consists of small stanzas, called “Methods” or “Functions” depending on what language you use. Each of these verses must be constructed in such a way that it is efficient, tightly-crafted, and effective. And like a poem, there are rules that dictate how it should be shaped. There is beauty in a clever Function.

But the real beauty of code goes further than poetry. Because it re-uses itself. Maybe its more like music, where a particular measure is repeated later in the song, and through its familiarity, it adds to the shape of the whole piece. Functions are like that, in that they’re called throughout the software. Sometimes they repeat within themselves, in iterations, like the repeating patterns you see in nature.

And when the pieces are added up, each in itself a little work of art, they make, if programmed properly, a whole that is much more than a sum. Its is an intertwined, and constantly moving piece of art.

And when the pieces are added up, each in itself a little work of art, they make, if programmed properly, a whole that is much more than a sum. Its is an intertwined, and constantly moving piece of art.

As programmers, we add things called “log messages” so that we can see these parts working together, because without this output, the flow of the data through the different rungs and branches we put together is so fluid that we can’t even observe it and, like trying to fathom the number of stars in the sky, it is difficult to even conceptualize visually the thousands of interactions a second that your code is causing. And we need to do this, because next comes a Quality Assurance Engineer (or QA) who tries to break your code, question your decisions, and generally force you to do better than what you thought was your best.

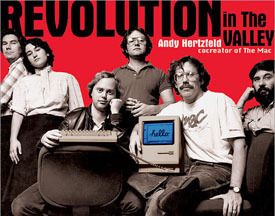

I truly believe that code is an art form. One that only a small portion of the population can appreciate. Sure anyone can walk into the Louvre and appreciate the end result of a Da Vinci or a Van Gogh, but only a true artist or student of art can really understand the intricacy of the work behind it.

Similarly, most people can recognize a good piece of software when they use it (certainly anyone can recognize a bad piece of software) but it takes a true artist, or at least an earnest student, to understand just how brilliant — or how wretched — the work behind it is.

And always, as you weave your code, you have to be prepared to change it, to re-use it, to re-contain it, to re-purpose it in ways that you can’t have planned for. Because that is the nature of your art form — always changing and advancing.

Publishing and Documenting

Its been said that a scientist or researcher must “publish or perish.” The same is true of a software developer. A brilliant piece of code, if not used, is lost. Within months it will become obsolete, or replaced, or usurped, and your efforts will become meaningless, save for the satisfaction of having solved a problem on your own.

So after months of wearing jeans, chugging caffeine, cluttering your desk with sketches and reference material, you clean yourself up, put on a nice pair of pants, comb your hair, and sell again. Although most organizations have a sales force and a marketing department, a savvy customer will invariably want technical details that a non-coder can’t supply. As a lead developer on a project, it falls to you to instill confidence, to speak articulately and passionately about the appropriateness and worth of your solution.

Again, as before, pride is a weakness here, because no matter how good you are, someone will always ask if your software can do something it can’t — users are never really satisfied. So you think back to the design process, you remind them when they had a part in the decisions, and you attempt to impress upon them respect for the solution you have now, while acknowledging that there will always be a version 2.0.

And you write and you teach. Not so much in my current job, but in one previous, as a lead developer it was my responsibility to educate people on the uses of our technology — to come up with ways to express the usefulness of a project without boring people with too many technical details.

One of the best parts of software development, a part that I miss since its not within my present job description, is getting up in front of people — once they’ve accepted your solution — and teaching them how to use it and apply it. Taking them beyond the basic functionality and showing them the tricks and shortcuts and advanced features that you programmed in, not because anyone asked you for them, but because you knew in your gut they should be there.

And Repeat…

Then there’s a party, a brief respite, where you celebrate your victory, congratulate those who’ve worked on parallel projects, and express your deepest gratitude for your peers who’ve lent their own particular area of expertise to your project… And you start again. Because like I’m sure any sports team feels, you are only as good as your latest victory.

So do I fix computers? Often its easier or more expedient to hack together a solution to a problem on my own — certainly the I.T. Department is becoming something of a slow-moving dinosaur in an age where computers aren’t the size of buildings, and most of us are comfortable re-installing Windows on our own — but that’s not a part of my job description.

No, I, like my peers, produce art. Functional, useful, but still beautiful, art. We are code poets, and it is our prose that builds the tools people use every day.

However, unlike most other artists, we’re usually paid pretty well for our work 😉

Post-script to Slashdotters (did you RTFA?!)

A few things to clarify here, based on the comments on the site:

- The intent was not to gripe about Canada’s standards for the term “engineer.” I only pointed that out the difference between my home country, and my current country of employ. I prefer the term “software developer” myself, but it doesn’t really matter to me. It was only one sentence in a 2100+ word article — hardly my thesis!

- The intent was also not to be pompous or fuel my own ego, it was to describe, as eloquently as I knew how, what most of us on Slashdot are. Although the stigma is going away, us geeky types tend to be considered only that: geeks. When really there is art and beauty to what we do. I’m not even as skilled a programmer as I imagine most are, but I wanted to lend my prose to our art because I believe it is valuable. But flame on, if you must! However, please note that I do have a degree, I work for a big company that prides itself in the quality of its products, I have 8 years of real experience, and I have a great life outside of work. This was a mental exercise, so please be nice!

I appreciate feedback — even critical, as long as its intelligent, so drop me a line if you have anything to say other than “you’re a douchebag” and “stop whining that you’re not an engineer.” But please do read the article first!

The other day, while ostensibly playing a rousing game of Halo 3 online, we were debating over the headsets about the affect technology has on our society: our communities, our relationships, our connectedness. Adam took the side that believes that technology is forcing a wedge between individuals, destroying a sense of community, and creating a generation of lonely, depressed individuals.

The other day, while ostensibly playing a rousing game of Halo 3 online, we were debating over the headsets about the affect technology has on our society: our communities, our relationships, our connectedness. Adam took the side that believes that technology is forcing a wedge between individuals, destroying a sense of community, and creating a generation of lonely, depressed individuals. – Blogs: Once the domain of uber-geeks with coding skills, baby blogs are sprouting up all over the Internet. There are all different kinds — from the bullet-point blog post to the photo blog — and yes, there are a few truly awful ones, but this technology is to human communication in the 2000s as the printing press was in the 1400s. Publication of works is now something that belongs to the individual.

– Blogs: Once the domain of uber-geeks with coding skills, baby blogs are sprouting up all over the Internet. There are all different kinds — from the bullet-point blog post to the photo blog — and yes, there are a few truly awful ones, but this technology is to human communication in the 2000s as the printing press was in the 1400s. Publication of works is now something that belongs to the individual.

A piece of software starts, before any code is written, as an idea or as a problem to be solved. Its a constraint on a plant floor, a need for information, a better way to work, a way to communicate, or a way to play. It is always tied to a human being — their job, their entertainment… their needs. A good process will explore this driving factor well. In the project I’m wrapping up now I felt strongly, and my employer agreed with me, that to understand what we needed to do, we’d have to go to the customer and feel their pain. We’d have to watch them work so we could understand their constraints. And we’d have to explore the other solutions out there to the problem we were trying to solve.

A piece of software starts, before any code is written, as an idea or as a problem to be solved. Its a constraint on a plant floor, a need for information, a better way to work, a way to communicate, or a way to play. It is always tied to a human being — their job, their entertainment… their needs. A good process will explore this driving factor well. In the project I’m wrapping up now I felt strongly, and my employer agreed with me, that to understand what we needed to do, we’d have to go to the customer and feel their pain. We’d have to watch them work so we could understand their constraints. And we’d have to explore the other solutions out there to the problem we were trying to solve.

And when the pieces are added up, each in itself a little work of art, they make, if programmed properly, a whole that is much more than a sum. Its is an intertwined, and constantly moving piece of art.

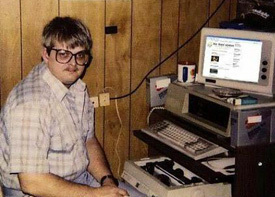

And when the pieces are added up, each in itself a little work of art, they make, if programmed properly, a whole that is much more than a sum. Its is an intertwined, and constantly moving piece of art. In my field, and in my experience, the inverse is frequently true. The more unruly the hair, or crazy the beard; the more out-of-date the wardrobe; the larger the glasses, the more likely it is that the individual is a sheer genius, and the most brilliant coder you’ve ever met.

In my field, and in my experience, the inverse is frequently true. The more unruly the hair, or crazy the beard; the more out-of-date the wardrobe; the larger the glasses, the more likely it is that the individual is a sheer genius, and the most brilliant coder you’ve ever met.