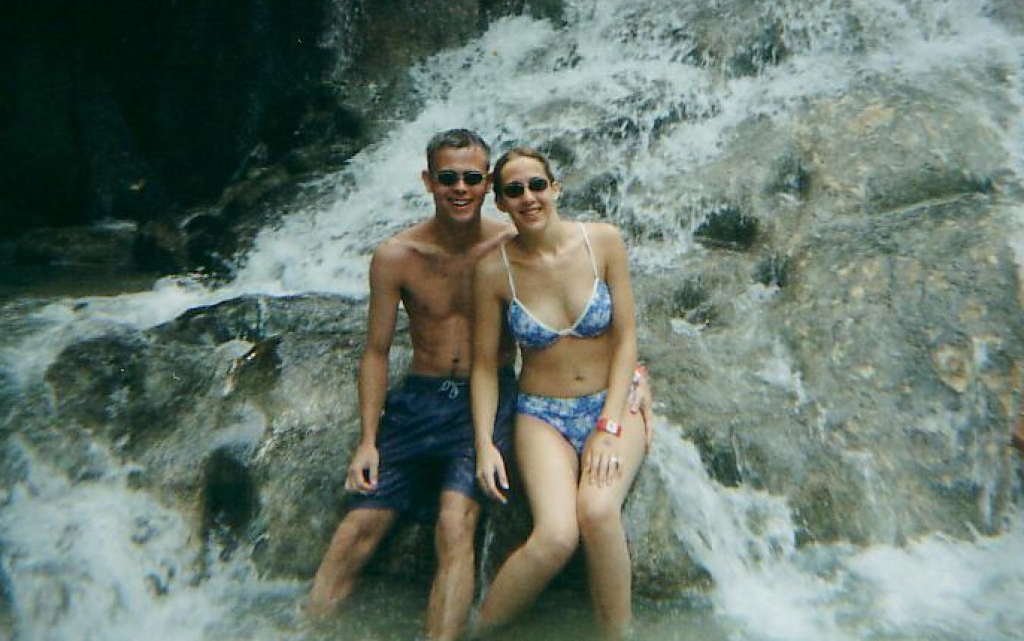

Nic and I got our first camera together a few months before our wedding — it was also our last film camera. I had a few digital cameras, but at the time, the quality was low and the prices still high, and we wanted really good pictures that would last. So we got a good scanner to go along with our film, and resolved to began preserving memories.

The subsequent economies of scale for digital cameras, and later the rapidly improving quality of phone cameras resulted in a proliferation of photographs — and many hours spent on a strategy for organizing and storing them. This got even more complicated with 3 new digital archivists when our kids got phones and began photographing and recording everything.

The result is more than 140GB of photos over 20+ years, organized in folders by year, then by month. The brief metadata I can capture in a folder name is rarely enough to be able to quickly pinpoint a particular memory, but wading through the folders to find something is often a fun walk down memory lane anyway.

Since I first started out archiving photos, a number of technology solutions have come along claiming to be able to do it better. Flickr, Google Photos, iPhoto, Amazon Photos all made bold assertions that they could automatically organize photos for you, in exchange for a small fee for storing them. The automatic organization always sucked, and the fees were usually part of an ecosystem lock-in play. It seems nothing has been able to beat hierarchical directory trees yet.

Since I first started out archiving photos, a number of technology solutions have come along claiming to be able to do it better. Flickr, Google Photos, iPhoto, Amazon Photos all made bold assertions that they could automatically organize photos for you, in exchange for a small fee for storing them. The automatic organization always sucked, and the fees were usually part of an ecosystem lock-in play. It seems nothing has been able to beat hierarchical directory trees yet.

Still 140GB is a lot, and 20 years of memories can’t be saved on a single hard drive — there’s too much risk. Some kind of bulk back-up mechanism is important. For the past 8 years, we’ve used Microsoft’s OneDrive. Their pricing is the best, and their sync clients work well on most platforms. They don’t try to force any organization on you, it kinda just works.

Lately, though, they’ve begun playing into the “ecosystem lock” trap. The macOS client is rapidly abandoning older (and more functional) versions of the OS. OneDrive is priced most attractively if you also subscribe to Office, which is also moving to the consumer treadmill model of questionable new features requiring newer hardware. It seems that in order to justify the subscription software model, vendors need us to abandon our hardware every 3-4 years. This artificial obsolescence must be the industry’s answer to the fact that consumer computing innovation has plateaued, and there’s no good reason to replace a computer less than 10 years old any more — and many good reasons not to.

In short, while I’m not unhappy with OneDrive, and consider the current incarnation of Microsoft to be one of the more ethical tech giants, it was high time to begin exploring alternatives. If you’re sensing a theme here lately, it stems from a realization that if us nerds willingly surrender all our data to big companies, then what hope does the average person have of privacy in this connected age?

Fortunately, like with most other tech, there are open source alternatives. Some are only for those who can DIY, but a significant number are available for the less tech savvy willing to vote with their wallets. Both NextCloud and OwnCloud offer sync clients that are highly compatible with a range of operating systems and environments. Both are available as self-host and subscription systems — from a range of providers. At least for now, I’ve decided to self-host OwnCloud in Azure. This is largely because I get some free Azure as a work-perk. If that arrangement changes in the future, I’m very likely to subscribe to NextCloud provided by Hetzner, a privacy-conscious European service that costs less than $5.

Right now, our total synced storage needs for the family are under 300GB. I have another terabyte of historical software, a selection of which will remain in a free OneDrive account. The complete 1.3TB backup is on dual hard drives, one always stored offsite. This relatively small size is due to the fact that we stopped downloading video as soon as streaming services became a viable paid alternative — although that appears to be changing.

Right now, our total synced storage needs for the family are under 300GB. I have another terabyte of historical software, a selection of which will remain in a free OneDrive account. The complete 1.3TB backup is on dual hard drives, one always stored offsite. This relatively small size is due to the fact that we stopped downloading video as soon as streaming services became a viable paid alternative — although that appears to be changing.

I started making money on computers as a teen by going around and fixing people’s computers for them. Most made the same simple mistakes, were grateful for help, and were generally eager to learn. In 2022, I’m afraid we’ve all just surrendered to big tech — we’ve decided its too hard to learn to manage our digital lives, so we let someone else do it; in exchange, we’ve stopped being customers and instead we’ve become the products. With our digital presence being so important, maybe its time consumers decided we’re not for sale.